One morning last January, Metra foreman Robert Tellin was startled as he peered out the window of his office at Elgin’s commuter station. There, Tellin saw a man standing in the center of the tracks, just as the PA announced an approaching train.

One morning last January, Metra foreman Robert Tellin was startled as he peered out the window of his office at Elgin’s commuter station. There, Tellin saw a man standing in the center of the tracks, just as the PA announced an approaching train.

Hurrying outside, Tellin asked the man what he was doing on the tracks. The man responded: I want to die.

Quickly, Tellin grabbed the man and safely pulled him from the rails, seconds before the train arrived.

It was a heroic effort on the part of Tellin, whom Metra’s board of directors honored with a resolution in March.

Unfortunately, for every moment of heroism there are many more moments of tragedy across the Chicago area’s vast network of railroad tracks. It seems every few weeks a Metra line is shut down due to a “pedestrian accident.” One just incident occurred last Thursday when a woman was struck in Northbrook by an Amtrak train, which shares the same tracks.

Indeed, death on the tracks is a problem that is particularly endemic to the Chicago area.

According to the Federal Railroad Administration, in 2015 there were 32 suicides-by-train in Illinois. That’s one-tenth of the national total. And as the Chicago Tribune reported in 2014, the metro area itself has a higher incidence of suicides by train than the national average.

Research by Northwestern University professor Ian Savage found that 47 percent of railroad-pedestrian fatalities in the Chicago area were apparent suicides, versus 30 percent nationally.

One reason, Savage explained, is simply because the Chicago area has a greater prevalence of tracks and trains. The city is the largest rail hub in North America and is served by all six of the major Class I freight railroads, as well as by Amtrak passenger trains and Metra, one of the nation’s busiest commuter rail networks.

The more trains and tracks, the more opportunities for tragedy, not just for those seeking to take their own lives, but anyone who risks taking a shortcut across tracks or trespasses along right-of-way.

Over the past four decades, overall fatalities at highway-rail crossings have dropped significantly across the U.S. In 1980, more than 800 people died when trains struck vehicles at crossings, data show. By last year, however, crossing fatalities had dropped by nearly three-quarters nationally.

Rail safety experts credit “the three E’s” for this decrease: engineering, including improved crossing-gate technology; education by advocacy groups like Operation Lifesaver; and tougher enforcement by local authorities to deter motorists and pedestrians from trying to beat trains by ignoring signals and going around gates.

But the numbers have not been positive when it comes to fatalities involving trespassers on railroad tracks, including people who attempt to commit suicide by train. Since 1980, deaths attributed to trespassing – someone taking a shortcut across tracks, for example — and suicide have nearly doubled in the U.S., to almost 800 a year.

What’s to be done to reduce deaths by suicide and trespassing?

Metra says it started a program last fall through which 1,000 employees, including engineers, conductors and station agents have been trained to identify individuals who appear in distress or possibly suicidal. Employees are given guidance to take appropriate action to intervene. Metra also monitors social media to any references to suicide by train and says it has intervened a couple of times to alert police when it has seen tweets threatening suicide.

The training goes over suicide myths and facts, behavioral clues and other warning signs, and advises employees on how to approach these individuals. Tellin credited the program with helping him respond successfully in January, Metra spokesman Michael Gillis said.

Other experts say more can be done.

As the Tribune reported in 2014, some commuter rail agencies in cities like Boston, New York and Toronto have taken further steps to partner with local suicide prevention organizations and posting 24/7 hotline numbers at stations and locations where deaths have occurred.

Any last-minute intervention or distraction that takes someone’s mind off a crisis can prevent someone from intentionally stepping in front of a train, experts say.

“At a time when anyone is vulnerable or overwhelmed, you want something there to give them a reason to pause or know there’s another way,” Roberta Hurtig, then-executive director of Samaritans, a nonprofit group that works with Boston’s commuter rail agency, told the Tribune.

There is clear evidence of suicide “hot spots,” or clusters of incidents in DuPage and Lake Counties, Northwestern’s Savage found.

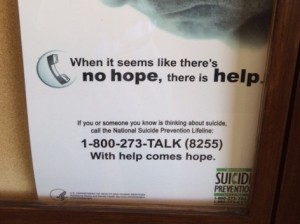

In Villa Park and Lombard, local officials and Operation Lifesaver have worked together to post signs along the Union Pacific/Metra tracks to help avert suicides. The signs say “There is help. Call us,” and list the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline phone number, 800-273-TALK (8255).

The Rotary Club of Naperville Sunrise recently posted signs at the suburb’s 5th Avenue Metra station stating “You are not alone” and listing the Lifeline number.

But unlike those other railroads, Metra has not chosen to adopt this type of partnership on a systemwide basis.

“We continue to monitor suicide prevention efforts by other railroads, and so far a clear consensus has not yet emerged that these efforts succeed in reducing the number of suicides along railroad tracks,” Metra’s Gillis said. “We are paying close attention to developments.”

On Thursday, Sept. 13, the DuPage Railroad Safety Council will host a daylong conference targeting “Tragedy on the Tracks” at the Drake Hotel in Oak Brook. Several nationally known experts are scheduled to make presentations, including Savage and others from DePaul University, Stanford, the University of Illinois, and the Volpe National Transportation Systems Center in Cambridge, Mass.

The council was formed 22 years ago by Dr. Lanny Wilson, whose daughter, Lauren, was killed at a Hinsdale rail crossing when the car she was riding in tried to beat a train. The council has long advocated for including more and improved gates and warning signals at crossings, tougher enforcement efforts to discourage violators, and heightened public awareness of the risk and danger of racing a train.

Encouraged by the drop in highway-rail crossing fatalities, Wilson said more attention must now be placed on eliminating trespass and suicide deaths by adapting the same strategies.

“Our conference is a call to action,” Wilson said. “We have the audacity to dream that Sept. 15, 2016 will be the historic day when the trespass and suicide numbers will begin their decline like the highway/rail crossing collision deaths have dropped.”

More information is available at www.dupagerailsafety.org

— Richard Wronski

2 comments